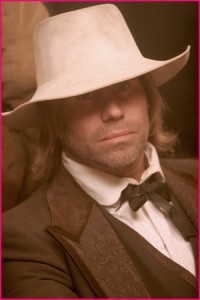

James O’Brien

Hi, James, it was great meeting you in LA last year, and Thank you for giving me the opportunity to interview you. I am very honored to have you join my website, Ninjagirl.

Hi, James, it was great meeting you in LA last year, and Thank you for giving me the opportunity to interview you. I am very honored to have you join my website, Ninjagirl.

Tomoko, it was great to meet you too last year in my hometown of Venice. I’m glad to support Ninjagirl and anyone like you who takes such an interest in indie movies. We’d love to take the film to Japan!

1. Your new film ‘Western Religion’ is to be released soon and it comes on the tail of your previous road trip film ‘Wish You Were Here’. Can you talk about your experience making ‘Wish You Were Here’?

Wish You Were Here was my second feature. It had been awhile since my first, Venice Bound, a crime caper film back in the glorious indie 16mm mid 90’s. I hooked up with my old friend Gary Kohn, one of the producers and stars of Venice Bound. He got me a job on a horror flic he was producing in this mountain town called Idyllwild. My producing partner on Western Religion, Louie Sabatasso was on that gig, doing the same thing as me, a cleaner like Harvey Keitel from Pulp Fiction. We became fast friends. Lou kept saying we should make our own movie– go on the road and do something with Gary. A lot had to do with Louie’s enthusiasm. Enthusiasm is the lifeblood of indie film. It precedes money as the most valuable resource. And Louie had never done an indie feature before so he was a true believer. All we needed was the notion and we were off to the races again.

Wish You Were Here was my second feature. It had been awhile since my first, Venice Bound, a crime caper film back in the glorious indie 16mm mid 90’s. I hooked up with my old friend Gary Kohn, one of the producers and stars of Venice Bound. He got me a job on a horror flic he was producing in this mountain town called Idyllwild. My producing partner on Western Religion, Louie Sabatasso was on that gig, doing the same thing as me, a cleaner like Harvey Keitel from Pulp Fiction. We became fast friends. Lou kept saying we should make our own movie– go on the road and do something with Gary. A lot had to do with Louie’s enthusiasm. Enthusiasm is the lifeblood of indie film. It precedes money as the most valuable resource. And Louie had never done an indie feature before so he was a true believer. All we needed was the notion and we were off to the races again.

2. What inspired you to make the film? Did you find inspiration in your own life for the script?

Hanging out in the trailer on the horror flic, Louie shared with me his dramatic experiences involved in getting sober. Truth as we well know, can be stranger than fiction. I thought it all made for a great story. Though I didn’t have the same connection to that world of recovery as Louie, I think everyone can relate on some level to the struggle of addiction. Also, Gary is one of my oldest, closest friends in LA, and he’s been sober since I’ve known him. So I thought the best bet was to write characters very similar to Gary and Lou and let them play off of the reality of their own lives in the context of a greater story. Lou’s character became Dean, a guy who exits a rehab in Venice at the start of the film, with nowhere to go and nothing left to lose. Gary became Neal, a concert promoter too busy to deal with anything but the fast track of work. The names are a subtle nod to Neal Cassidy/Dean Moriarty of On the Road, since I knew that’s where we’d be headed soon, on a cross country tear. Every road movie needs a girl on the run and we sure got one, played brilliantly by Arrowyn Ambrose. The core of the film is about forgiving that one key person in your life that allows you both to heal emotionally and move on with your life in a more enlightened fashion.

3. How did this experience inform Western Religion? Do you feel your experience with filming on the road influenced the way you produced Western Religion?

The major takeaway from WYWH, in so far as it relates to Western Religion, was that we pulled off the extreme challenge of a cross country film production out of an RV with 10 people, lining up all of our locations on the fly right before we started shooting. All in 19 days. I remember right before the show thinking, this is crazy, the last time I drove across country it took me 11 days and I wasn’t shooting a feature film. The schedule was locked in, since we had to get Arrowyn on a flight from New York to Australia at the end of those 19 days. Having done a lot of location work in LA, I knew how hard it would be to get all of our spots with basically zero budget, a fifty here, a hundred there maybe. We had a lot of angels on the road. The honkytonk bar, Robert’s Western World, in Nashville comes to mind. I booked that at 2AM the night before right after the owner jumped off stage with his band. He said yes right away. I could never get away with that in LA. But we were like the Blues Brothers: “We’re on a mission from God.” You have to work yourself into that state sometimes on indie movies in order to see them though. Often because you don’t have the motivation of getting paid. It’s only afterwards that you think, how the hell did we do that?

The major takeaway from WYWH, in so far as it relates to Western Religion, was that we pulled off the extreme challenge of a cross country film production out of an RV with 10 people, lining up all of our locations on the fly right before we started shooting. All in 19 days. I remember right before the show thinking, this is crazy, the last time I drove across country it took me 11 days and I wasn’t shooting a feature film. The schedule was locked in, since we had to get Arrowyn on a flight from New York to Australia at the end of those 19 days. Having done a lot of location work in LA, I knew how hard it would be to get all of our spots with basically zero budget, a fifty here, a hundred there maybe. We had a lot of angels on the road. The honkytonk bar, Robert’s Western World, in Nashville comes to mind. I booked that at 2AM the night before right after the owner jumped off stage with his band. He said yes right away. I could never get away with that in LA. But we were like the Blues Brothers: “We’re on a mission from God.” You have to work yourself into that state sometimes on indie movies in order to see them though. Often because you don’t have the motivation of getting paid. It’s only afterwards that you think, how the hell did we do that?

4. During the production of Western Religion, the National Park Service shut down. Since you had planned on filming at Paramount Ranch, located in the National Park system, it required a sudden change in plans. What were you thinking when it happened? How did you deal with this setback?

On Western Religion when the National Parks where closed, we didn’t panic. On WYWH we were kicked out of every bus station we went to, and only pieced together that scene by shooting enough at three different stations before we got the boot. But Western Religion was a much bigger production. Instead of five actors in the film, we had a cast of 60. And instead of a run and gun road movie, this was a Western, with all of the sets, gear and costuming that entails. It could have been a disaster. Everything was lined up at the Paramount Ranch and we were only a couple weeks from day one of principal photography. But having done three features already, and many other short films, I knew that a movie tends to take on a life of its own. In fact, that’s the very thing that you are looking for, that the movie itself starts to tell you what it wants to be. Western Religion wanted to be done in a different way than we could do it on the traditional set of Paramount Ranch. And it wound up being the best possible thing that could have happened. Peter Sherayako stepped in and offered up his ranch at Caravan West in Agua Dulce, where we built our own historically accurate Wild West tent city from scratch. Variety found out and did an article on it. We all got to live up in the mountains while making the film. The indie gods smiled on us. Fortune favors the bold, I reckon.

On Western Religion when the National Parks where closed, we didn’t panic. On WYWH we were kicked out of every bus station we went to, and only pieced together that scene by shooting enough at three different stations before we got the boot. But Western Religion was a much bigger production. Instead of five actors in the film, we had a cast of 60. And instead of a run and gun road movie, this was a Western, with all of the sets, gear and costuming that entails. It could have been a disaster. Everything was lined up at the Paramount Ranch and we were only a couple weeks from day one of principal photography. But having done three features already, and many other short films, I knew that a movie tends to take on a life of its own. In fact, that’s the very thing that you are looking for, that the movie itself starts to tell you what it wants to be. Western Religion wanted to be done in a different way than we could do it on the traditional set of Paramount Ranch. And it wound up being the best possible thing that could have happened. Peter Sherayako stepped in and offered up his ranch at Caravan West in Agua Dulce, where we built our own historically accurate Wild West tent city from scratch. Variety found out and did an article on it. We all got to live up in the mountains while making the film. The indie gods smiled on us. Fortune favors the bold, I reckon.

5. You managed to collect a unique and eclectic cast of actors for the film. How did you cast for the film? Did you have experience working with the actors previously?

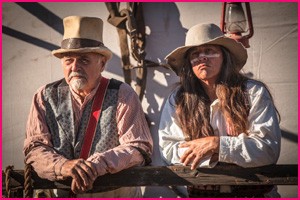

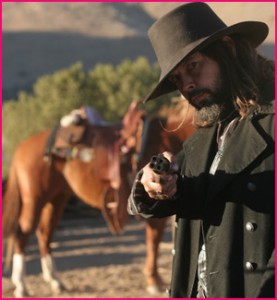

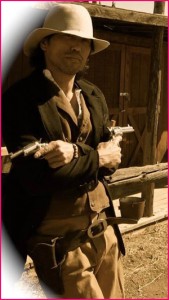

The acting talent came together very organically. Some actors I wrote parts for specifically, which I’m fond of doing. Louie Sabatasso plays the pansexual Dandy Salt Peter in WR and Gary Kohn plays the robber turned preacher Saint John. A new friend, Sean Joyce, was working on a demolition job with Gary, Lou and I so I wrote him the part of Bobby Shea, the traveling carpenter. The female lead of Bootstrap Bess I wrote for Holiday Hadley, who I knew as a singer songwriter, but felt she’d be great playing a gun fighting, card playing, whiskey swilling, brothel running madame. The inimical James Cotton, who plays the Barnum Bailey like Harvard Gold, I met at a birthday party for our DP Morgan Schmidt. I told James that night I’d have something for him. He said he always wanted to do a western, which seems like a bucket list thing for a lot of actors. Sometimes casting one actor, like my friend Tony Herbert, an Irishman playing the English journalist Edward James, led to the casting of another, like his friend, Peter Shinkoda, who plays the railroad refugee Chinaman Dan. Peter wound up leading us to Merik Tadros, our Prince Zain Mohammed. Both Peter and Merik were friends with Claude Duhamel, who we cast in the 11th hour a week before the shoot began. Claude found out from them about the show and sent me an audition on-line just as I had the phone in my hand to call another actor. Fortunately I didn’t, because Claude is amazing in the film, in a very important lead role as Anton Stice, the epitome of the dark outlaw. To fill out the rest of the cast, I turned to my good friend Scott Donovan, who’s been in many of my films and plays Marshal Stone in Western Religion. He set up a casting session at his studio in Hollywood. One wild character actor Frankie Ray showed up at that session in full western regalia with several of his friends. They were such colorful characters that I cast them all.

The acting talent came together very organically. Some actors I wrote parts for specifically, which I’m fond of doing. Louie Sabatasso plays the pansexual Dandy Salt Peter in WR and Gary Kohn plays the robber turned preacher Saint John. A new friend, Sean Joyce, was working on a demolition job with Gary, Lou and I so I wrote him the part of Bobby Shea, the traveling carpenter. The female lead of Bootstrap Bess I wrote for Holiday Hadley, who I knew as a singer songwriter, but felt she’d be great playing a gun fighting, card playing, whiskey swilling, brothel running madame. The inimical James Cotton, who plays the Barnum Bailey like Harvard Gold, I met at a birthday party for our DP Morgan Schmidt. I told James that night I’d have something for him. He said he always wanted to do a western, which seems like a bucket list thing for a lot of actors. Sometimes casting one actor, like my friend Tony Herbert, an Irishman playing the English journalist Edward James, led to the casting of another, like his friend, Peter Shinkoda, who plays the railroad refugee Chinaman Dan. Peter wound up leading us to Merik Tadros, our Prince Zain Mohammed. Both Peter and Merik were friends with Claude Duhamel, who we cast in the 11th hour a week before the shoot began. Claude found out from them about the show and sent me an audition on-line just as I had the phone in my hand to call another actor. Fortunately I didn’t, because Claude is amazing in the film, in a very important lead role as Anton Stice, the epitome of the dark outlaw. To fill out the rest of the cast, I turned to my good friend Scott Donovan, who’s been in many of my films and plays Marshal Stone in Western Religion. He set up a casting session at his studio in Hollywood. One wild character actor Frankie Ray showed up at that session in full western regalia with several of his friends. They were such colorful characters that I cast them all.

6. I like the costumes in WR, was it really hard to select the costumes? Were you involved with selecting the costumes?

The costumes for Western Religion were certainly a challenge as we had so many actors, 60 in total, and they had to meet us out in a remote location, far from the comforts of Hollywood. Fortunately, we were in very good hands with our Costume Designer Nikki Pelley and her assistant Alisha Needham. I had some concerns beforehand as to whether two people were enough on such a big show, but Nikki and Alisha really came through. I love the look they put together. Nikki even sewed some character finger puppets on the fly for a scene that was supposed to involve marionettes. The puppets didn’t show, so Nikki did us one better and made them herself. On my end, I hit up a thrift store in Hermosa beach a few days before the production and bought some additional costuming touches like Salt Peter’s beaver coat and Bobby Shea’s suit. I also gave Anton Stice my very own black overcoat, which lent a little of my own personal style to the film. We have Pete Sherayko to thank for setting us up with our killer designers Nikki and Alisha, who for the most part culled their garments from Pete’s personal collection. He’s a stickler for period detail.

The costumes for Western Religion were certainly a challenge as we had so many actors, 60 in total, and they had to meet us out in a remote location, far from the comforts of Hollywood. Fortunately, we were in very good hands with our Costume Designer Nikki Pelley and her assistant Alisha Needham. I had some concerns beforehand as to whether two people were enough on such a big show, but Nikki and Alisha really came through. I love the look they put together. Nikki even sewed some character finger puppets on the fly for a scene that was supposed to involve marionettes. The puppets didn’t show, so Nikki did us one better and made them herself. On my end, I hit up a thrift store in Hermosa beach a few days before the production and bought some additional costuming touches like Salt Peter’s beaver coat and Bobby Shea’s suit. I also gave Anton Stice my very own black overcoat, which lent a little of my own personal style to the film. We have Pete Sherayko to thank for setting us up with our killer designers Nikki and Alisha, who for the most part culled their garments from Pete’s personal collection. He’s a stickler for period detail.

7. Were the actors given a script? Did the story change along with the ever changing set being constructed?

The script for Western Religion was very tight, unlike WYWH, which had a lot of improv and felt like we were writing it as we went along on the road. With WR we shot the script, essentially. With so many things in flux, if the script was one of them we would have been doomed. I think the fact that Western Religion had a solid screenplay helped attract some of the cast and gave us a good head start with the general enthusiasm for the project. The one scene we had to rewrite was the ending, where in the original I had a buckboard wagon riding off of a cliff, in epic Thelma and Louise style. There was no way we were shooting that on an indie budget, so we had to come up with something else. Returning a bit to the style of WYWH, a writing jam session with Louie and Gary led to the scene we have now, which works much better thematically. That’s not to say there was no improv on the film. You always have to be open to that and it’s always there in a sense. But having come off a heavy improv flic, it was refreshing to be able to lean on what was on the page for the most part.

The script for Western Religion was very tight, unlike WYWH, which had a lot of improv and felt like we were writing it as we went along on the road. With WR we shot the script, essentially. With so many things in flux, if the script was one of them we would have been doomed. I think the fact that Western Religion had a solid screenplay helped attract some of the cast and gave us a good head start with the general enthusiasm for the project. The one scene we had to rewrite was the ending, where in the original I had a buckboard wagon riding off of a cliff, in epic Thelma and Louise style. There was no way we were shooting that on an indie budget, so we had to come up with something else. Returning a bit to the style of WYWH, a writing jam session with Louie and Gary led to the scene we have now, which works much better thematically. That’s not to say there was no improv on the film. You always have to be open to that and it’s always there in a sense. But having come off a heavy improv flic, it was refreshing to be able to lean on what was on the page for the most part.

8. The fact that the film was shot on location gives the production a feeling of ‘authenticity’, as though the viewer was actually observing life on the frontier. What did you do to ensure the audience would have the feeling they “have dust in their eyes”?

We shot Western Religion out in Agua Dulce, on a set constructed under the guidance of western historian Peter Sherayko, who came into prominence on the great western film Tombstone, both as Texas Jack Vermillion, and as the technical supervisor of the period detail, particularly the weapons. He’s basically an entire self contained Western world. Hire him and you’ve got a movie. When I had the idea of doing this film, our Director of Photography Morgan Schmidt and our Make-Up FX guy Michael Dinetz, each recommended someone who had all of this gear for making westerns, the whole kit and kaboodle, in truck containers. At first I thought they were talking about two different people. But when I found out it was the same guy, Peter Sherayko, I had to give him a call. When I went out to his ranch with Louie and Sean Joyce, we were blown away by all of the western artifacts he has, everything you could imagine. It was like time traveling to another era. I knew at that point, beyond the shadow of a doubt, there was no one else we could make the film with. I held firm on that. He became an even bigger element once we lost our location. In our first meeting when the Paramount set fell through, Pete took out all of these old historical photos of western tent cities. He said we could build something like that on his land and that no one has ever done that before. Against all odds was kind of the theme of our little movie, so we had to roll with it. Doing it with Caravan West, Sherayko’s company, on sets we constructed allowed us to control our environment in a way we never could at Paramount Ranch, which had so many restrictions. U

We shot Western Religion out in Agua Dulce, on a set constructed under the guidance of western historian Peter Sherayko, who came into prominence on the great western film Tombstone, both as Texas Jack Vermillion, and as the technical supervisor of the period detail, particularly the weapons. He’s basically an entire self contained Western world. Hire him and you’ve got a movie. When I had the idea of doing this film, our Director of Photography Morgan Schmidt and our Make-Up FX guy Michael Dinetz, each recommended someone who had all of this gear for making westerns, the whole kit and kaboodle, in truck containers. At first I thought they were talking about two different people. But when I found out it was the same guy, Peter Sherayko, I had to give him a call. When I went out to his ranch with Louie and Sean Joyce, we were blown away by all of the western artifacts he has, everything you could imagine. It was like time traveling to another era. I knew at that point, beyond the shadow of a doubt, there was no one else we could make the film with. I held firm on that. He became an even bigger element once we lost our location. In our first meeting when the Paramount set fell through, Pete took out all of these old historical photos of western tent cities. He said we could build something like that on his land and that no one has ever done that before. Against all odds was kind of the theme of our little movie, so we had to roll with it. Doing it with Caravan West, Sherayko’s company, on sets we constructed allowed us to control our environment in a way we never could at Paramount Ranch, which had so many restrictions. U p in the wilds of Agua Dulce, we got to live in the trailers on set. Never could have gotten away with that at Paramount, where there was a strict curfew. We got to live like we were back in the Wild West in a sense. It definitely contributed to the flavor of the movie. The night before day one I had a real moment out there in the wilderness. I was walking around on the land and ended up at this stable, where these horses where chilling out in the moonlight. As I’m looking into the eyes of this one horse, this guy comes out of the darkness dressed in old time cowboy long pajamas. He says, “can I help you?” I told him I was shooting a western in the mountains not far from here. He says, “Western Religion?” I said, “yeah.” He told me his name was Kevin McNiven, owner of America’s Cowboy, and these were the horses for the show, all nine of them. He had just driven from Wyoming. In that moment I knew we’d be okay. We had horses. I could shoot for a few days with the horses and actors out in the territory while we caught up with building sets.

p in the wilds of Agua Dulce, we got to live in the trailers on set. Never could have gotten away with that at Paramount, where there was a strict curfew. We got to live like we were back in the Wild West in a sense. It definitely contributed to the flavor of the movie. The night before day one I had a real moment out there in the wilderness. I was walking around on the land and ended up at this stable, where these horses where chilling out in the moonlight. As I’m looking into the eyes of this one horse, this guy comes out of the darkness dressed in old time cowboy long pajamas. He says, “can I help you?” I told him I was shooting a western in the mountains not far from here. He says, “Western Religion?” I said, “yeah.” He told me his name was Kevin McNiven, owner of America’s Cowboy, and these were the horses for the show, all nine of them. He had just driven from Wyoming. In that moment I knew we’d be okay. We had horses. I could shoot for a few days with the horses and actors out in the territory while we caught up with building sets.

9. You even received a tip of the hat from Henry Parker, the renowned Western chronicler. What was it like having him on set? What did he have to say about the production of “Western Religion”?

Having western chronicler Henry Parker show up on set to do a story on the production was a real honor. Henry wrote a great piece on us in Henry’s Western World, which he later followed up on. Of course, we had to put him in the movie. Having your own serial story by a guy who knew the genre inside and out was fantastic. We were just hitting our stride at the end of the first week when he showed up. He interviewed a number of us and really captured the feel of the production at that juncture. Fortunately, he didn’t come the first few days because there wasn’t anything to come to.

10. Your film will be included later this year at the Cannes Film Festival. Talk about what it is like to be included in a festival with such a renowned history. How do you see this opportunity influencing your work moving forward?

It’s great to be premiering the film at the Cannes Film Festival. 20 years ago

It’s great to be premiering the film at the Cannes Film Festival. 20 years ago

I was there for the international premiere of my first film Venice Bound. Gary Kohn was there for that, so it’s a full circle thing. Since then I’ve learned a lot. We’ll be there with our sales agent Automatic Entertainment. Michael Lurie and Jeffery Giles are great agents and they really know how to handle a picture like this. So we’re pleased to launch the film at the best festival in the world. There’s nothing quite like Cannes. The French really know how to celebrate films, both the independents and the big productions. Our whole plan with Western Religion was to create a film that was a bridge between micro budget indies and the Hollywood style tent pole flic. The international audience will let us know if we succeeded. Here’s to dust in yer eyes!

11.You’ve mentioned Sergio Leone and his production of “Spaghetti Westerns”. Are you a fan of his work? Who is your favorite character from the history of the Western film?

As far as my taste in the genre of Westerns, Clint Eastwood would be a primary influence, both with the films he made with Sergio Leone and later work like Unforgiven. The Outlaw Josey Wales was for sure a favorite growing up and Clint directed that one. I had a vision of myself directing a western, but instead of guns like Josey Wales, I would have Super 8 cameras. As far a Sergio Leone’s films go, they were very independently styled productions, off Hollywood, and set in these rough and tumble towns. They had a gritty feel and a great style, particularly in the extreme close-ups on character’s eyes, played to perfect effect in The Good, the Bad and the Ugly. I liked the way Sergio brought his own take to the American Western and wound up the most significant influence on the genre, beyond Clint Eastwood himself.

12. You’ve said that you started writing this film with the title, “Western Religion”. This seems counterintuitive, and I’m curious to know what the creative process is like taking a film title and turing it into a full scale production. Can you talk about your creative process?

I had it in mind for awhile that I wanted to follow up Wish You Were Here with something much bigger production wise, either a Fantasy film or a Western. The idea I had for the western was gunfighters with battling philosophies. I carried the idea around for several months until it hit me one day as I was swinging a sledge hammer on the demolition job: Western Religion. I told Louie and he started riffing about the character he wanted to play, which we quickly named Salt Peter. I went home that night and wrote the main character list, which was fifteen strong, with many other supporting characters. On this one, the character descriptions really told the story. The script took a few months to write, but came relatively easily. Ideally, the Fantasy film I am doing next will be a similar process. It’s called: Warrior, Mage, Thief. Those are the three main archetypes for fantasy role playing games. Of course, with my films there will be a twist on it. I’m developing it for Virtual Reality technology, as well as the traditional film approach. As Ed Wood said: “My next one will be even better!”

I had it in mind for awhile that I wanted to follow up Wish You Were Here with something much bigger production wise, either a Fantasy film or a Western. The idea I had for the western was gunfighters with battling philosophies. I carried the idea around for several months until it hit me one day as I was swinging a sledge hammer on the demolition job: Western Religion. I told Louie and he started riffing about the character he wanted to play, which we quickly named Salt Peter. I went home that night and wrote the main character list, which was fifteen strong, with many other supporting characters. On this one, the character descriptions really told the story. The script took a few months to write, but came relatively easily. Ideally, the Fantasy film I am doing next will be a similar process. It’s called: Warrior, Mage, Thief. Those are the three main archetypes for fantasy role playing games. Of course, with my films there will be a twist on it. I’m developing it for Virtual Reality technology, as well as the traditional film approach. As Ed Wood said: “My next one will be even better!”

13. I would love to hear if you have some message to all the readers of my website?

Western Religion is an international film, both in cast and aesthetic. It draws characters from around the globe to take part in a legendary poker tournament. We had actors with a Japanese background like Peter Shinkoda, as well as others from Ireland, Australia, New Zealand, the Middle East, Russia, Canada and, of course, the US. We also had full blooded Native Americans from the Apache tribe, like Sam Bearpaw. When I was asked before the shoot where I would most like to see the film show after it was finished, Japan came to mind. My Father was once the President of the US affiliate of a Japanese company called Plus USA. He would take trips to Japan all the time and show my three sisters and I the pictures when he got home. I’ve always wanted to go there, but especially with one of my films, since its always so interesting to see what another cultures take on the film is. It allows you to look at it with new eyes. Perhaps, if we are lucky, the film will play at a theater in Tokyo!

Western Religion is an international film, both in cast and aesthetic. It draws characters from around the globe to take part in a legendary poker tournament. We had actors with a Japanese background like Peter Shinkoda, as well as others from Ireland, Australia, New Zealand, the Middle East, Russia, Canada and, of course, the US. We also had full blooded Native Americans from the Apache tribe, like Sam Bearpaw. When I was asked before the shoot where I would most like to see the film show after it was finished, Japan came to mind. My Father was once the President of the US affiliate of a Japanese company called Plus USA. He would take trips to Japan all the time and show my three sisters and I the pictures when he got home. I’ve always wanted to go there, but especially with one of my films, since its always so interesting to see what another cultures take on the film is. It allows you to look at it with new eyes. Perhaps, if we are lucky, the film will play at a theater in Tokyo!

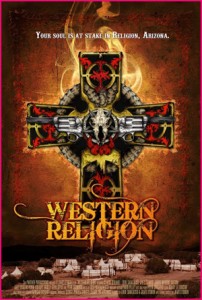

Western Religion Set To Make Its World Premiere In Cannes

edited by Anthony Heller

You must be logged in to post a comment Login